PANKRATION, PANIC, AND THE FRAGILE ILLUSION OF CONTROL

by Sezer Ali | DEC 25, 2025

ART & IDENTITY

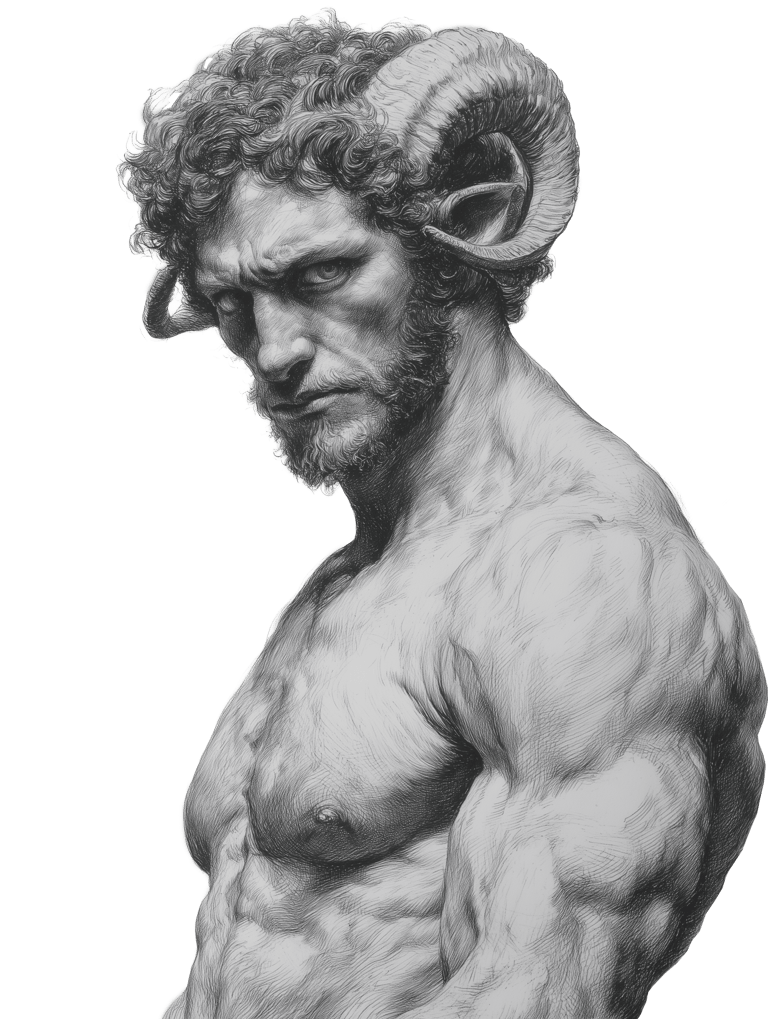

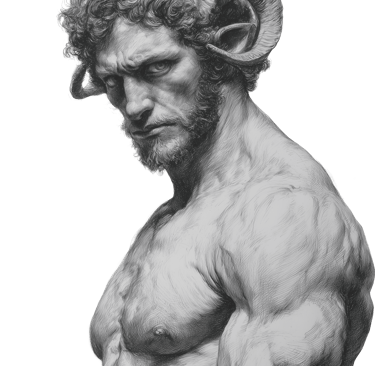

PAN

The body where identity breaks

The body was our first language.

Before representation, before naming, before identity, the body existed as a fact.

My interest in how bodies communicate meaning began early, during my education at an art school, where the human figure was never treated as a neutral form. Anatomy was not merely structure; it was tension, intention, vulnerability. A torso could imply power or fragility. A posture could indicate discipline, desire, or fear. Later, this fascination deepened through translated critical texts in Bulgarian periodical publications—most notably the work of Igor Semyonovich Kon, whose writings challenged the idea of the male body as a natural given. Kon viewed masculinity as a cultural construct rather than a biological imperative, contending that male physicality is influenced, governed, and interpreted by social norms rather than mere instinct. As he observed, masculinity is not inherited; it is constructed, rehearsed, and constantly tested. (Kon, 2003)

This perspective becomes particularly revealing when viewed through the lens of antiquity—not the polished antiquity of marble statues and ideal proportions, but one marked by struggle, exposure, and risk. Among the ancient Greek athletic practices, pankration stands apart. A hybrid of wrestling and striking, it was a combat discipline with minimal rules and maximal physical demand. Classical sources describe it not as a spectacle, but as an agon—a contest in which the stakes were endurance, submission, and survival. (Vernant, 1983) In pankration, the body was stripped of symbolic excess. There was no pose to maintain, no image to preserve. Only reaction remained.

It is here that Pan (Πάν) enters—not as a decorative mythological figure, but as an archetype of rupture. Pan represents sudden fear, unanticipated panic, and the dissolution of control. Neither fully human nor animal, Pan occupies thresholds: between civilisation and wilderness, reason and impulse, and form and collapse. As Jean-Pierre Vernant reminds us, Greek culture did not deny chaos; it lived in constant negotiation with it. Order existed precisely because its dissolution was always possible. (Vernant, 1983) Pan is the embodiment of that potential.

This article is not an exercise in mythological analysis, nor a historical account of an ancient sport. Instead, it uses pankration as a conceptual framework and Pan as a philosophical pressure point to ask a contemporary question: what remains of identity when the image fails? In a culture where bodies are endlessly visualised, curated, and disciplined—through fitness regimes, wellness ideologies, and digital representation—the ancient combat arena exposes an uncomfortable truth. Beneath identity as narrative and art as form, there persists a body that does not seek meaning but endurance.

PANKRATION AND THE REFUSAL OF THE IMAGE

In classical art, the body is resolved.

In pankration, it is interrupted.

Ancient Greek sculpture presents the male body as balanced: proportioned, composed, and seemingly self-contained. Even in moments of tension, the sculpted figure appears to be in control, arrested in an idealised instant of potential rather than collapse. This visual language has profoundly shaped Western ideas of bodily perfection, reinforcing the belief that form is both attainable and stable. The lived experience of the ancient body—exposed, trained, fatigued, and wounded—was in stark contrast to its marble counterpart.

Pankration occupies this dissonance. As a combat practice, it rejects the logic of representation. In a chokehold, there is no ideal posture, and there is no heroic symmetry during the moment of submission. The body folds, contorts, and fails. In this sense, pankration does not merely depict the body; it actively resists being considered an image. The fighter’s concern is not how the body appears, but whether it endures. Visibility becomes secondary to survival.

This refusal of the image is crucial. Art historian Richard Neer has argued that classical form functions as a stabilising device—a way of containing the volatility of the human body within intelligible limits. (Neer, 2010) Pankration, by contrast, exposes what form seeks to conceal: imbalance, panic, and vulnerability. The combat arena becomes a space where the body exceeds aesthetic legibility. It cannot be read; it can only be experienced.

Such moments reveal a deeper truth about identity. When the body is pushed to its limits, the symbolic frameworks that normally define the self—status, reputation, even name—lose their authority. What remains is a corporeal presence stripped of narrative. Michel Foucault’s analysis of the disciplined body helps illuminate this condition. While ancient athletics were embedded within systems of training and regulation, pankration marks a threshold where discipline collapses into exposure. (Foucault, 1977) The body, no longer governed by representation, becomes a site of raw immediacy.

Pan’s presence is felt precisely here. Pan's presence is felt not as a figure watching from the margins, but as a force within the body itself. Panic is not fear imagined; it is fear enacted. It arrives when the body no longer obeys conscious intention, when breath shortens, muscles tighten, and reason recedes. In pankration, panic is not failure—it is revelation. It reveals the distance between the body's image and the body's lived experience.

For contemporary viewers, this refusal of the image resonates powerfully. Today's visual culture demands consistency, optimisation, and legibility. Bodies are curated through training, filtered through screens, and disciplined into recognisable forms of identity. Yet practices that foreground exhaustion, impact, and risk—whether in combat sports or performance art—continue to attract fascination precisely because they fracture this visual order. They expose the body where it resists becoming a symbol.

Pankration reminds us that the body precedes its representation. Before it becomes art, before it signifies identity, the body persists as a material condition—unruly, responsive, and finite. This piece is not a nostalgic return to antiquity but a confrontation with something unresolved in the present: the fear that beneath our carefully constructed images lies a body that cannot be fully controlled.

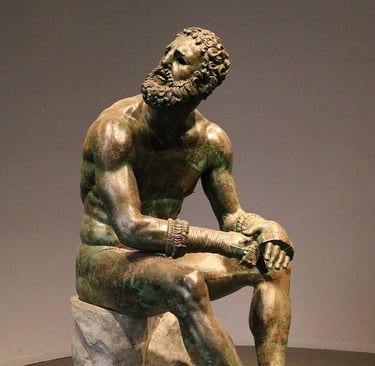

Fig. 1. The Boxer at Rest (also known as The Terme Boxer), Hellenistic Greek bronze, c. 1st century BCE.

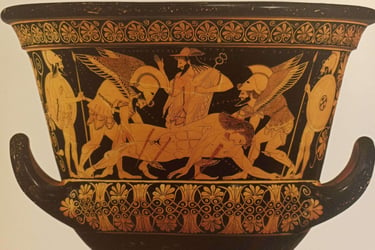

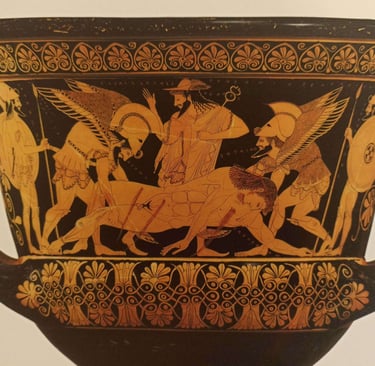

Fig. 2. Attic red-figure krater attributed to the Euphronios Painter, c. 550–500 BCE.

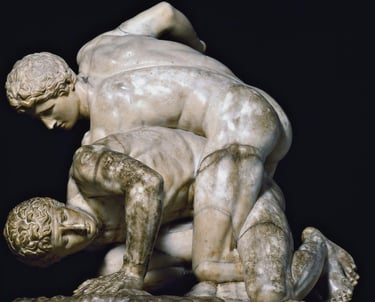

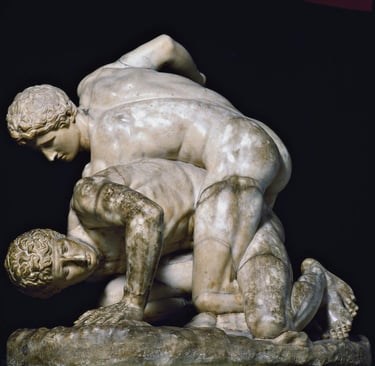

Fig. 3. Wrestlers (Uffizi Wrestlers), Roman marble sculpture, 1st century BCE.

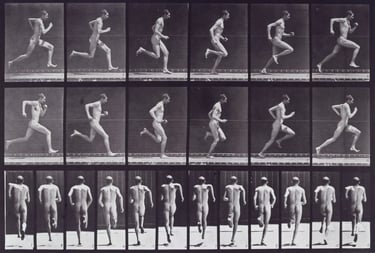

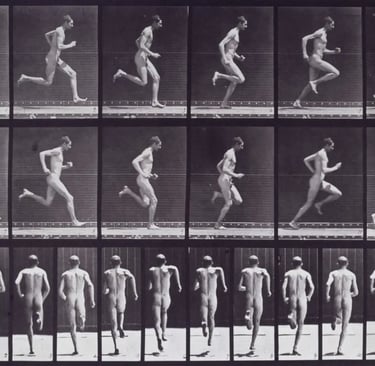

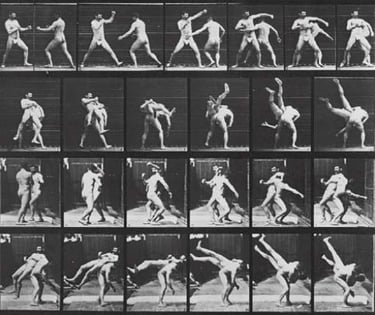

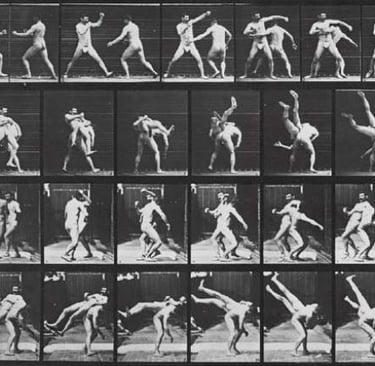

Fig. 4. Eadweard Muybridge, Wrestling / Athletic Motion Studies, from Animal Locomotion, 1880s

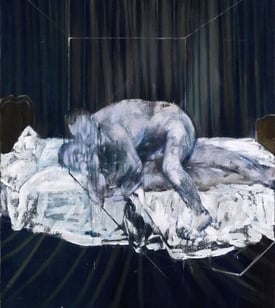

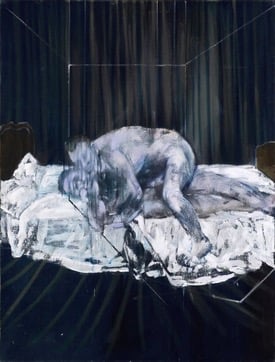

Fig. 5. Francis Bacon, Two Figures, 1953.

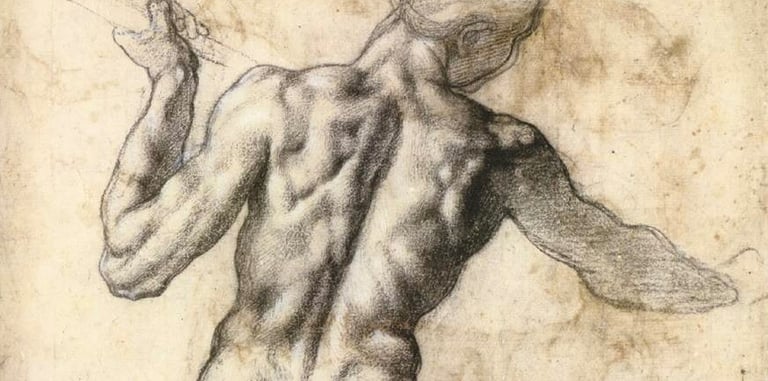

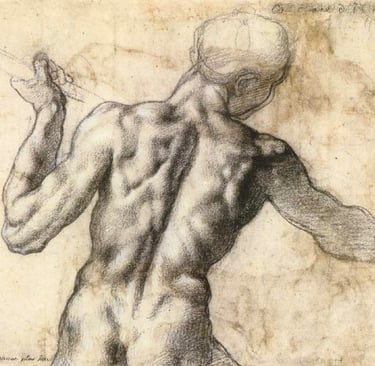

Fig. 6. Michelangelo Buonarroti, Studies for the Battle of Cascina: Male Nude, Seen from the Rear (verso), c. 1504.

PAN, PANIC, AND THE BODY BEYOND CONTROL

Panic is not imagined.

It is felt.

The Greek word panikon deima describes a sudden, contagious fear—an eruption that bypasses reason and takes hold of the body before thought can intervene. This is the fear attributed to Pan: not a distant terror, but an embodied shock. Unlike the controlled anxieties of civic life, panic dissolves structure. It interrupts language, posture, and intention. The body reacts before the mind understands.

In ancient thought, this loss of control was not accidental. Pan belonged to the margins of the polis—to mountains, forests, and borderlands, where the assurances of civilisation weakened. His hybrid form destabilised the logic of classification: neither god nor beast, neither culture nor nature. As classicist Philippe Borgeaud notes, Pan represents a divine figure who resists integration into the ordered pantheon precisely because he embodies excess and unpredictability. (Borgeaud, 1988) His presence signals the breakdown of measure.

Pankration stages this breakdown within the body itself. The fighter enters the contest trained, disciplined, and prepared, yet panic remains unavoidable. Breath is restricted, balance collapses, and pain overwhelms orientation. In these moments, the body ceases to be an instrument of the self and becomes its limit. Identity, normally sustained through coherence and control, fractures under pressure. What emerges is not heroism, but exposure.

This exposure reveals a deeper anxiety embedded in Western culture: the fear of the body’s autonomy. From Plato onwards, philosophers expressed unease at the body's resistance to rational command, treating it as a source of disorder that requires regulation. (Plato, 2005) Pan personifies this anxiety. He is not violent by nature; he is destabilising. He appears when the body refuses to remain silent, when instinct interrupts intention.

In contemporary contexts, panic is often pathologised—treated as a malfunction rather than a signal. Nevertheless, as cultural theorist Brian Massumi suggests, effect precedes cognition. The body feels before it understands. (Massumi, 2002) Panic exposes this sequence brutally. It reveals that control is always provisional, that identity is sustained only as long as the body cooperates.

This is why Pan remains unsettling. He does not attack; he interrupts. He does not destroy form; he reveals its fragility. In pankration, panic is not an external threat but an internal event—a moment when the self confronts its limits. The body becomes unfamiliar territory, no longer aligned with the narratives imposed upon it.

To encounter Pan, then, is not to encounter mythology but to experience a rupture in certainty. It is to recognise that beneath identity as performance and art as composition lies a body capable of disobedience. Panic marks the point at which the illusion of mastery falters, and something older, less articulate, but profoundly real, emerges in its place.

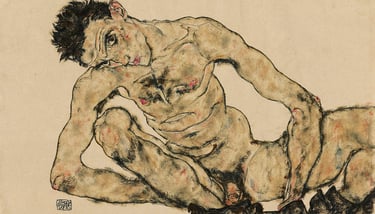

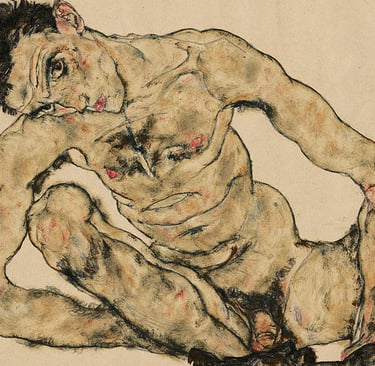

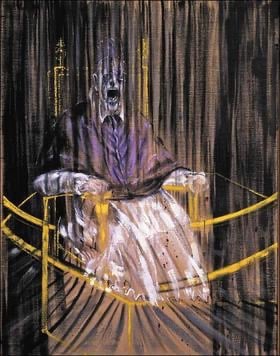

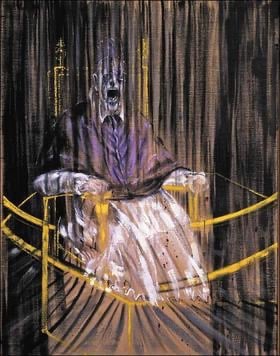

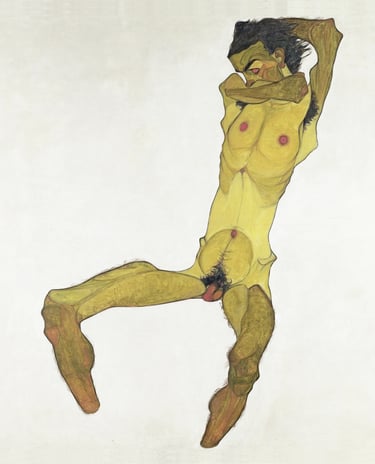

Fig. 7. Hendrick van Balen the Elder, in collaboration with Jan Brueghel the Elder, Pan Pursuing Syrinx, c. 1615. Fig. 8. Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Bacchus and Ariadne, 1520–1523. Fig. 9. Henry Fuseli, The Nightmare, 1781. Fig. 10. Egon Schiele, Nude Self-Portrait, 1916. Fig. 11. Francis Bacon, Study after Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X, 1953.

COMBAT, RITUAL, AND THE CONTEMPORARY BODY

Before it was entertainment, combat was ritual.

Before it was ritual, it was necessity.

In antiquity, athletic contests were embedded within religious and civic frameworks. Pankration, despite its violence, was not a form of spectacle designed for consumption but a structured confrontation with physical limits. It functioned as a rite of passage—a test through which the body was publicly exposed and privately transformed. Victory mattered, but endurance mattered more. The contest did not merely produce winners; it produced altered bodies.

Ritual, as anthropologist Victor Turner reminds us, is defined by liminality—a threshold state in which participants are temporarily removed from social order. (Turner, 1969) In pankration, this liminal condition is enacted through bodily risk. The fighter enters a space where normal hierarchies are suspended, where identity is no longer guaranteed by name or status but negotiated through physical persistence. The body undergoes transformation, serving as both subject and object.

This ritual dimension resonates strongly with contemporary performance practices. Throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, artists have repeatedly turned to the body as a site of endurance, vulnerability, and confrontation. These works resist passive spectatorship. They demand attention not through beauty, but through duration, risk, and exposure. Like pankration, they place the body in situations where control is provisional and meaning emerges through sustained physical presence rather than representation.

Crucially, such practices disrupt the boundaries between art and lived experience. Art historian Amelia Jones argues that body-centred performance collapses the distance between the viewer and subject, forcing an encounter with the material reality of another body. (Jones, 1998) This collapse mirrors the logic of combat: the impossibility of aesthetic detachment. One cannot observe a body under strain without acknowledging its mortality.

In contemporary culture, combat has re-emerged in sanitised and commodified forms—regulated sports, televised events, and branded disciplines. These formats promise authenticity while carefully managing risk, offering controlled access to violence without its full consequences. Yet the appeal of these practices lies precisely in their residual unpredictability. They flirt with the possibility that something might go wrong, that the body might exceed its script.

Here, Pan returns—not as chaos unleashed, but as chaos contained. The ritual persists, but its edges are softened. Training regimens, safety protocols, and visual narratives frame the body as robust, optimised, and heroic. The rupture moment is suppressed: panic, disorientation, and the body's refusal to act as expected.

Nevertheless, these moments cannot be fully erased. They surface in exhaustion, injury, and silence. They mark the limits of ritualistic control and remind us that the body remains an unstable participant in its representation. Combat—whether ancient or contemporary—continues to function as a threshold where identity is tested, not affirmed. (Poliakoff, 1987)

In this sense, ritual does not resolve panic; it negotiates with it. It provides a structure within which the body may approach its vulnerability without collapsing entirely. Pankration and contemporary performance share this fragile balance. Both acknowledge that the body cannot be fully mastered—only temporarily held in form.

This image documents a moment from Rhythm 0, a six-hour performance in which Marina Abramović offered her body to the audience as a site of unrestricted action. By relinquishing agency and accepting vulnerability as a condition of presence, Abramović transforms the body into a terrain of endurance, risk, and ethical confrontation. The work resists representation in favour of lived exposure: meaning emerges not through form or image, but through duration, uncertainty, and the unstable dynamics between performer and spectator. Positioned within this article, the image functions as a contemporary analogue to pankration — a space where control is provisional, boundaries are negotiated in real time, and the body becomes both medium and threshold.

Fig. 12. Attic red-figure vase depicting pankration, 5th century BCE.

Fig. 13. Eadweard Muybridge, Wrestling Studies, 1880s. Photographic motion studies.

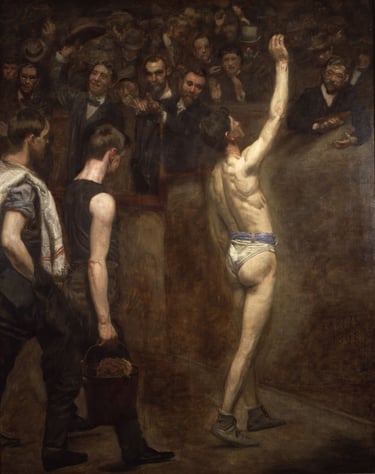

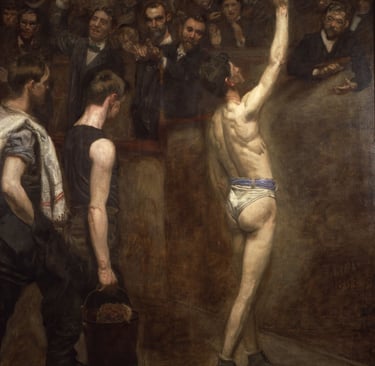

Fig. 14. Thomas Eakins, Salutat, 1898. Oil on canvas.

Fig. 15. Contemporary MMA bout (video still).

Fig. 16. Santiago Sierra, 160 cm Line Tattooed on 4 People, 2000. Performance documentation.

Fig. 17. Marina Abramović, Rhythm 0, 1974. Performance documentation.

THE RETURN OF PAN: Body Culture and the Illusion of Control

Pan never disappeared.

He was disciplined.

Contemporary body culture is built on the promise of mastery. Strength can be trained, endurance can be optimised; and vulnerability can be managed. Through fitness regimes, wellness ideologies, and digital self-representation, the body is framed as a project—measurable, improvable, and ultimately controllable. Identity, in turn, becomes inseparable from performance. To have a body is to demonstrate intention. This logic echoes what Michel Foucault describes as the productive operation of modern power, in which discipline does not repress the body but actively produces it through regimes of self-regulation and desire (Foucault, 1978).

Yet this culture of control is haunted by what it seeks to suppress. Behind routines for self-care and optimisation lies a persistent anxiety that the body may resist. Injury, exhaustion, and panic interrupt the narrative of progress. These moments expose the limits of discipline and recall the ancient tension between form and instinct. What returns is not chaos, but the awareness of its proximity.

The visual economy intensifies this tension. Bodies circulate endlessly as images—filtered, repeated, and evaluated. Social platforms reward coherence and legibility, reinforcing narrow ideals of strength, health, and desirability. As Susan Bordo observes, the contemporary body functions as a moral surface, where self-control is equated with virtue and deviation with failure (Bordo, 1993). The image becomes evidence of discipline.

Within this framework, panic is reinterpreted as malfunction. Anxiety is medicalised; fear is internalised; and physical breakdown is framed as a personal deficiency rather than a structural condition. Yet panic remains resistant to such narratives. It does not signal weakness; it signals excess—an overload of sensations beyond the body’s capacity to organise itself. Here, Brian Massumi’s understanding of affect is instructive: sensation precedes representation, and bodily intensity consistently exceeds systems of rational control (Massumi, 2002). Pan persists here, not as a threat, but as a reminder.

Art continues to confront this instability. Contemporary practices that foreground fatigue, repetition, and corporeal risk resist the smoothness of digital identity. They refuse the fantasy of seamless control, insisting instead on the body’s material limits. In doing so, they recover something fundamental: the recognition that identity is not anchored solely in representation but negotiated through lived experience.

This return of Pan is not a regression to savagery, nor a rejection of form. It is an ethical disturbance—a call to acknowledge the body as more than an image. In confronting panic, we encounter not failure, but truth: that control is always partial, and that identity, like the body itself, remains provisional.

To engage with Pan today is to accept uncertainty. It is to be recognised that beneath every curated image lies a body capable of resistance. In this recognition, art regains its critical function—not to idealise the body, but to expose the fragile conditions under which identity is sustained.

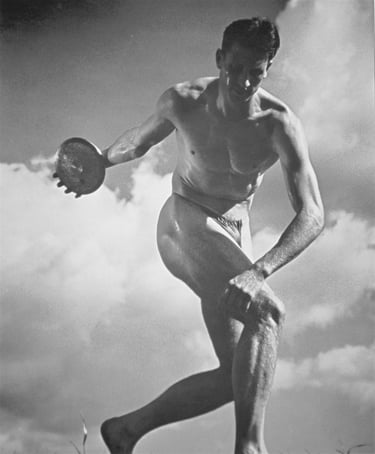

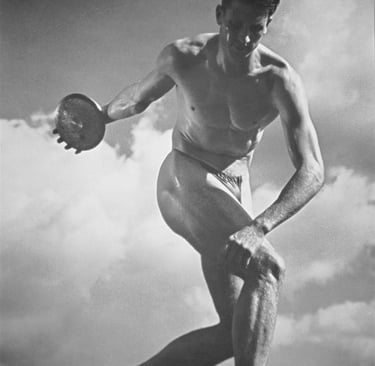

Fig. 18. Leni Riefenstahl, Olympia, 1938. Film stills.

Fig. 19. Francis Bacon, Three Studies for a Self-Portrait, 1979–1980. Oil on canvas.

Fig. 20. Cindy Sherman, Untitled Film Stills, 1977–1980. Photographic series.

Fig. 21. Amalia Ulman, Excellences & Perfections, 2014. Performance documentation (digital media).

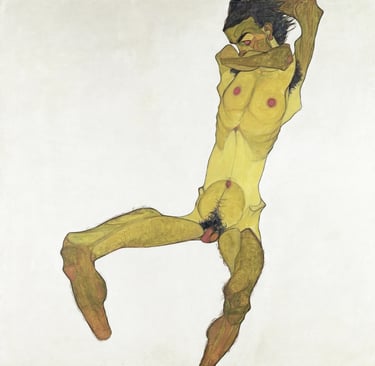

Fig. 22. Egon Schiele, Seated Male Nude (Self-Portrait), 1910. Oil on canvas.

In this early self-portrait, Schiele presents the male body as tense, exposed, and unsettled. The figure resists classical ideals of harmony and control, instead asserting vulnerability as a condition of presence. Angular limbs, distorted posture, and direct confrontation disrupt the image of mastery, revealing the body as a site of psychological intensity rather than aesthetic resolution. Positioned within this article, the work anticipates the modern collapse of bodily certainty: identity emerges not through ideal form, but through fragility, discomfort, and the refusal of composure.

Pan does not demand belief.

He demands recognition.

This essay has not sought to rehabilitate an ancient god, nor to romanticise violence or endurance. Instead, it has traced a tension that persists across time: the fragile balance between form and instinct, identity and exposure, and control and collapse. Pankration, as both practice and metaphor, reveals what is often obscured by representation—the body as a site of risk rather than display.

In a culture saturated with images, the body is rarely allowed to fail. It is encouraged to perform, improve, and signify. Panic disrupts this economy. It arrives without permission, suspending language and dissolving the carefully constructed narratives that sustain identity. In that suspension, something essential becomes visible: the body, not as a symbol, but as a condition.

Pan names this moment. He is not an external force, nor a relic of myth, but the presence that emerges when the illusion of mastery falters. His relevance today lies precisely in this interruption. Where identity is over-articulated, Pan introduces silence. Where form is fetishised, he exposes fragility.

To acknowledge Pan is to accept art and embrace identity. It is to approach both with greater honesty. Art, at its most critical, does not conceal the body’s limits—it stages them. Identity, at its most humane, does not deny vulnerability—it negotiates with it.

What remains, then, is not resolution, but attentiveness. Under every image, there is a body capable of resistance, beneath every narrative, there is a breath that may shorten, and beneath every form, there is the possibility of collapse. Recognising this does not lose meaning. We recover its weight.

References

Massumi, B., Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation, Durham: Duke University Press, 2002.

Bordo, S., Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Western Culture, and the Body, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

Borgeaud, P., The Cult of Pan in Ancient Greece, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988.

Foucault, M., Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, London: Penguin Books, 1977.

Foucault, M., The History of Sexuality, Volume 1: An Introduction, London: Penguin Books, 1978.

Jones, A., Body Art/Performing the Subject, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1998.

Kon, I. S., The Male Body: A New Look at Men in Public and in Private, New York: Harrington Park Press, 2003.

Massumi, B., Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation, Durham: Duke University Press, 2002.

Neer, R. T., The Emergence of the Classical Style in Greek Sculpture, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010.

Plato, Phaedrus, trans. C. J. Rowe, London: Penguin Classics, 2005.

Poliakoff, M. B., Combat Sports in the Ancient World: Competition, Violence, and Culture, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987.

Turner, V., The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure, Chicago: Aldine Publishing, 1969.

Vernant, J.-P., Myth and Thought among the Greeks, London: Routledge, 1983.

Images credit

Fig. 1. The Boxer at Rest (also known as The Terme Boxer), Hellenistic Greek bronze, c. 1st century BCE. Museo Nazionale Romano, Rome.

Fig. 2. Attic red-figure krater attributed to the Euphronios Painter, c. 550–500 BCE. Found in Cerveteri. Museo Nazionale Archeologico Cerite, inv. L.2006.10.

Fig. 3. Wrestlers (Uffizi Wrestlers), Roman marble sculpture, 1st century BCE. Copy after a lost Greek bronze original of the 3rd century BCE. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.

Fig. 4. Eadweard Muybridge, Wrestling / Athletic Motion Studies, from Animal Locomotion, 1880s (photographed c. 1872–1885).

Fig. 5. Francis Bacon, Two Figures, 1953. Oil on canvas.

Fig. 6. Michelangelo Buonarroti, Studies for the Battle of Cascina: Male Nude, Seen from the Rear (verso), c. 1504. Black chalk on paper.

Fig. 7. Hendrick van Balen the Elder, in collaboration with Jan Brueghel the Elder, Pan Pursuing Syrinx, c. 1615. Oil on copper.

Fig. 8. Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Bacchus and Ariadne, 1520–1523. Oil on canvas. National Gallery, London.

Fig. 9. Henry Fuseli, The Nightmare, 1781. Oil on canvas, 180 × 250 cm.

Fig. 10. Egon Schiele, Nude Self-Portrait, 1916. Watercolour and pencil on paper.

Fig. 11. Francis Bacon, Study after Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X, 1953. Oil on canvas, 153 × 118 cm. Des Moines Art Center, Des Moines.

Fig. 12. Attic red-figure vase depicting pankration, 5th century BCE.

Fig. 13. Eadweard Muybridge, Wrestling Studies, 1880s. Photographic motion studies.

Fig. 14. Thomas Eakins, Salutat, 1898. Oil on canvas.

Fig. 15. Contemporary MMA bout (video still).

Fig. 16. Santiago Sierra, 160 cm Line Tattooed on 4 People, 2000. Performance documentation.

Fig. 17. Marina Abramović, Rhythm 0, 1974. Performance documentation.

Fig. 18. Leni Riefenstahl, Olympia, 1938. Film stills.

Fig. 19. Francis Bacon, Three Studies for a Self-Portrait, 1979–1980. Oil on canvas.

Fig. 20. Cindy Sherman, Untitled Film Stills, 1977–1980. Photographic series.

Fig. 21. Amalia Ulman, Excellences & Perfections, 2014. Performance documentation (digital media).

Fig. 22. Egon Schiele, Seated Male Nude (Self-Portrait), 1910. Oil on canvas.